Spelling Sensitivity in Russian Speakers Develops by Early Adolescence

Scientists at the RAS Institute of Higher Nervous Activity and Neurophysiology and HSE University have uncovered how the foundations of literacy develop in the brain. To achieve this, they compared error recognition processes across three age groups: children aged 8 to 10, early adolescents aged 11 to 14, and adults. The experiment revealed that a child's sensitivity to spelling errors first emerges in primary school and continues to develop well into the teenage years, at least until age 14. Before that age, children are less adept at recognising misspelled words compared to older teenagers and adults. The study findings have been published in Scientific Reports.

By the time they finish primary school, children's reading of high-frequency words becomes automated. Behavioural studies measuring parameters like reaction time and error rates show that children at this age can reliably distinguish between words and letter strings resembling words.

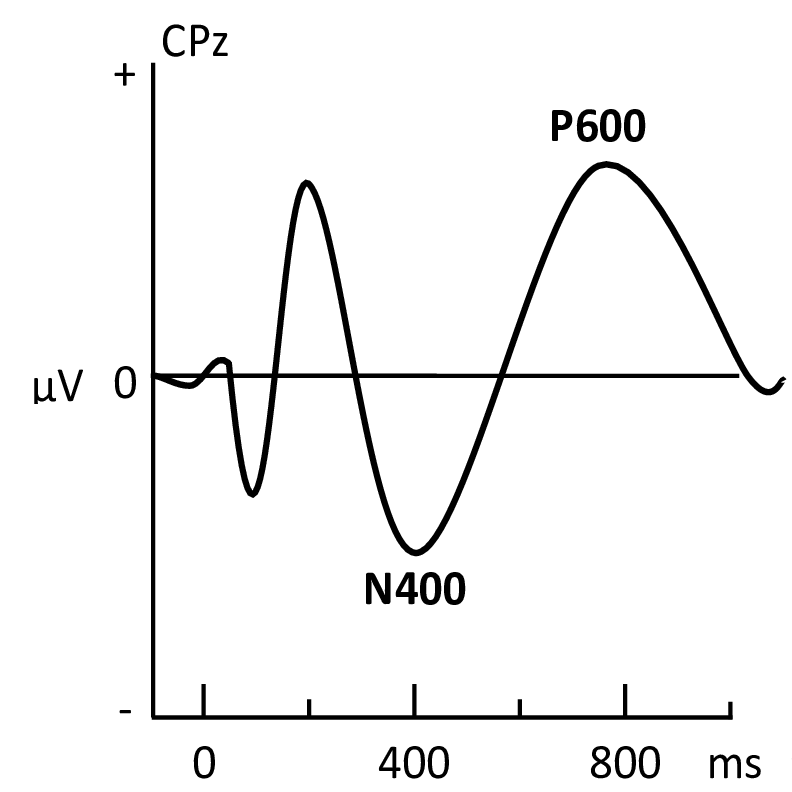

The event-related potential (ERP) method is a promising approach to examining the reading process in neurophysiological research. Event-related potentials are the brain's electrophysiological responses to perceptual events (such as specific sensations), cognitive events (like decision-making), or motor events (such as pressing a button).

The ERP method allows for assessing the brain's response to verbal stimuli and identifying time intervals—components within the ERP—associated with their processing. In primary school-age children, the ERPs in response to words and strings of non-letter symbols differ at 200 ms after presentation, but distinctions between words and meaningless strings of actual letters are detected much later, only after 400 ms. This indicates that such stimuli are more challenging for young children to process.

However, sensitivity to spelling patterns is not limited to the ability to distinguish words from meaningless letter sequences but also involves more complex skills related to recognizing spelling errors. The issue is that the neural bases underlying the development of orthographic sensitivity remain poorly understood.

Scientists at the RAS Institute of Higher Nervous Activity and Neurophysiology and the Centre for Cognition and Decision Making of the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience used electroencephalography (EEG) to investigate event-related potentials associated with spelling error recognition. The study involved children aged 8 to 10, early adolescents aged 11 to 14, and adults aged 18 to 39, all of them native speakers of Russian. None of the subjects experienced spelling difficulties.

The subjects were presented with words on a screen, some of which were spelled correctly while others were misspelled. The task was to determine whether the word on the screen was spelled correctly.

The experiment showed that all the groups successfully identified both correctly spelled and misspelled words. The average error rate, even among children aged 8 to 10, did not exceed 14%, although children had more incorrect answers and longer reaction times compared to early adolescents and adults.

Early adolescents and adults showed similar, though not identical, behavioural results. The response time to both types of stimuli and the percentage of erroneous responses to correctly spelled words did not differ between these groups. However, early adolescents were worse than adults at recognising misspelled words.

In adult participants, differences in ERPs between correctly and incorrectly spelled words were observed in two distinct time windows. This indicates that the recognition of spelling correctness by adults involves two ERP components: an early component around 400 ms and a later one of up to 600 ms, probably related to re-checking the spelling for errors.

In children aged 8 to 10, there were no differences in ERPs between correctly spelled and misspelled words. According to the researchers, this suggests that the ability to quickly recognise correct spelling is just beginning to develop at this age. Interestingly, in early adolescents, spelling recognition was reflected only at the later stage corresponding to the 600 ms component, ie they did not exhibit early differences related to automated spelling recognition.

The experiment revealed that a child's orthographic sensitivity first emerges in primary school and continues to develop well into the teenage years, at least until age 14. These findings contribute to our understanding of the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the mastery of Russian spelling and how these mechanisms evolve with age.

Leading Research Fellow, Centre for Cognition and Decision Making, Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience

In our study, adults and adolescents did not differ in their reaction times to any of the stimuli: both groups recognized correctly and incorrectly spelled words at similar speeds. This suggests that they likely employed similar reading and spelling recognition strategies. Nevertheless, the percentage of misidentified misspelled words was higher in early adolescents compared to adults, suggesting that spelling sensitivity is still developing at this age.

See also:

Scientists Find Out Why Aphasia Patients Lose the Ability to Talk about the Past and Future

An international team of researchers, including scientists from the HSE Centre for Language and Brain, has identified the causes of impairments in expressing grammatical tense in people with aphasia. They discovered that individuals with speech disorders struggle with both forming the concept of time and selecting the correct verb tense. However, which of these processes proves more challenging depends on the speaker's language. The findings have been published in the journal Aphasiology.

Implementation of Principles of Sustainable Development Attracts More Investments

Economists from HSE and RUDN University have analysed issues related to corporate digital transformation processes. The introduction of digital solutions into corporate operations reduces the number of patents in the field of green technologies by 4% and creates additional financial difficulties. However, if a company focuses on sustainable development and increases its rating in environmental, social, and governance performance (ESG), the negative effects decrease. Moreover, when the ESG rating is high, digitalisation can even increase the number of patents by 2%. The article was published in Sustainability.

Russian Scientists Develop New Compound for Treating Aggressive Tumours

A team of Russian researchers has synthesised a novel compound for boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT), a treatment for advanced cancer that uses the boron-10 isotope. The compound exhibits low toxicity, excellent water solubility, and eliminates the need for administering large volumes. Most importantly, the active substance reaches the tumour with minimal impact on healthy tissues. The study was published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences shortly before World Cancer Day, observed annually on February 4.

Scientists Discover Link Between Brain's Structural Features and Autistic Traits in Children

Scientists have discovered significant structural differences in the brain's pathways, tracts, and thalamus between children with autism and their neurotypical peers, despite finding no functional differences. The most significant alterations were found in the pathways connecting the thalamus—the brain's sensory information processing centre—to the temporal lobe. Moreover, the severity of these alterations positively correlated with the intensity of the child's autistic traits. The study findings have been published in Behavioural Brain Research.

Earnings Inequality Declining in Russia

Earnings inequality in Russia has nearly halved over the past 25 years. The primary factors driving this trend are rising minimum wages, regional economic convergence, and shifts in the returns on education. Since 2019, a new phase of this process has been observed, with inequality continuing to decline but driven by entirely different mechanisms. These are the findings made by Anna Lukyanova, Assistant Professor at the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences, in her new study. The results have been published in the Journal of the New Economic Association.

Russian Physicists Discover Method to Increase Number of Atoms in Quantum Sensors

Physicists from the Institute of Spectroscopy of the Russian Academy of Sciences and HSE University have successfully trapped rubidium-87 atoms for over four seconds. Their method can help improve the accuracy of quantum sensors, where both the number of trapped atoms and the trapping time are crucial. Such quantum systems are used to study dark matter, refine navigation systems, and aid in mineral exploration. The study findings have been published in the Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics Letters.

HSE Scientists Develop Application for Diagnosing Aphasia

Specialists at the HSE Centre for Language and Brain have developed an application for diagnosing language disorders (aphasia), which can result from head injuries, strokes, or other neurological conditions. AutoRAT is the first standardised digital tool in Russia for assessing the presence and severity of language disorders. The application is available on RuStore and can be used on mobile and tablet devices running the Android operating system.

HSE Researchers Discover Simple and Reliable Way to Understand How People Perceive Taste

A team of scientists from the HSE Centre for Cognition & Decision Making has studied how food flavours affect brain activity, facial muscles, and emotions. Using near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), they demonstrated that pleasant food activates brain areas associated with positive emotions, while neutral food stimulates regions linked to negative emotions and avoidance. This approach offers a simpler way to predict the market success of products and study eating disorders. The study was published in the journal Food Quality and Preference.

Russian Scientists Demonstrate How Disorder Contributes to Emergence of Unusual Superconductivity

Researchers at HSE University and MIPT have investigated how the composition of electrons in a superconductor influences the emergence of intertype superconductivity—a unique state in which superconductors display unusual properties. It was previously believed that intertype superconductivity occurs only in materials with minimal impurities. However, the scientists discovered that the region of intertype superconductivity not only persists but can also expand in materials with a high concentration of impurities and defects. In the future, these superconductors could contribute to the development of highly sensitive sensors and detectors. The study has been published in Frontiers of Physics.

HSE Scientists Take Important Step Forward in Development of 6G Communication Technologies

Researchers at HSE MIEM have successfully demonstrated the effective operation of a 6G wireless communication channel at sub-THz frequencies. The device transmits data at 12 Gbps and maintains signal stability by automatically switching when blocked. These metrics comply with international 6G standards. An article published on arXiv, an open-access electronic repository, provides a description of certain elements of the system.